Volume 2 Issue 4 April 2017

Volume 2 Issue 4 April 2017

Introduction

Much of what we call “cyber security” has its roots in an area of study and practice called “IT security”, which can be described as the protection of computer produced data and information and the associated protection of the infrastructure that makes possible the production, circulation, protection and curation of that data. However, the protection of data is no longer solely a question of IT security. The widespread adoption of digital technology across all strata of society and the increasing reliance by governments and industry to engage with citizens through digital media brings data protection into the realm of everyday life. If data protection is to make sense to people, IT security must clearly link to the human security needs and concerns that affect the individual. By approaching data protection in this way, we are looking at and responding to the challenge of the protection of data in a more holistic manner that includes the social, political, cultural and economic as well as the technical. This is often termed “cyber security”.

Engagement innovation

To understand cyber security in terms of what it means in people’s every day lives, Royal Holloway has developed a programme of creative security engagement methods that are playful, participative, open- ended and democratic, and are designed to support and structure conversations about digital security. They tease out how digital security relates to other parts of everyday life and create spaces in which people can actively discuss what cyber security means to them.

Case Study

Creative security methods have been deployed as part of e-safety programmes. For example, a community centre in a lower socio- economic area of Sunderland (North East England) wanted to include e-safety as part of an education and engagement programme designed for local young  people. The youth workers at the centre decided to focus on e-safety in the context of parental advice and the role they would like parents to play. It was agreed that creative methods would be used to enable this discussion. The researcher worked as a facilitator to help the youth workers and young people to develop the conversation through the co-creation of a wall collage.

people. The youth workers at the centre decided to focus on e-safety in the context of parental advice and the role they would like parents to play. It was agreed that creative methods would be used to enable this discussion. The researcher worked as a facilitator to help the youth workers and young people to develop the conversation through the co-creation of a wall collage.

The wall collage was co-constructed using the following process:

- The facilitator spent time observing the space and talking to the community.

- The facilitator worked with the youth workers and young people to create a series of open questions that reflected the e-safety interests of the community.

- The facilitator arrived at the Centre to start the project with some stimulus images and a large wall space.

- The facilitator worked alongside youth workers to ask the open questions with small groups of young people.

- The young people generated material for the wall collage.

The e-safety engagement was deemed a success because of the level of sustained engagement from the young people, showing that the topic was important to participants as well as being enjoyable as a mode of engagement. The young people produced a wall collage that demonstrated that they knew about e-safety issues but that there wasnot always a “right path”. Their narratives further showed that parents could be a security threat as well as a support.

The narratives gave youth workers an important steer on what type of e-safety support was most needed. This type of approach also enables information security researchers from different disciplinary backgrounds to collaborate by developing a shared understanding of the real-world security problems faced by a community. In particular, the approach enables a common understanding of the security concerns from the perspective of the individual.

March 2017

March 2017 Developers recognise a need to establish a consistent style regardless of the local version of a product. Later localisation is facilitated if a clear style guide for design is developed which includes the use of universal graphics and icons wherever possible.

Developers recognise a need to establish a consistent style regardless of the local version of a product. Later localisation is facilitated if a clear style guide for design is developed which includes the use of universal graphics and icons wherever possible.

In 2016, the Colombian Government had already envisaged a clear direction for the role of information and communication technologies (ICTs) to support post-conflict. According to

In 2016, the Colombian Government had already envisaged a clear direction for the role of information and communication technologies (ICTs) to support post-conflict. According to

India’s Aadhaar project is the biggest biometric project worldwide, and a good example of ICTs and datafication for development. Aadhaar provides a unique 12-digit number to those who enrol, capturing their fingerprints and iris scan. Its purpose is that of semplifying delivery of social services, enabling rapid identification of those entitled. Biometric details are linked to citizens’ data, hence a fingerprint is enough to access subsidised foodgrains or other benefits. My research on Aadhaar reveals two important points about the datafication of anti-poverty programmes. First is their technical rationale, and second are the political consequences that the new data architecture produces.

India’s Aadhaar project is the biggest biometric project worldwide, and a good example of ICTs and datafication for development. Aadhaar provides a unique 12-digit number to those who enrol, capturing their fingerprints and iris scan. Its purpose is that of semplifying delivery of social services, enabling rapid identification of those entitled. Biometric details are linked to citizens’ data, hence a fingerprint is enough to access subsidised foodgrains or other benefits. My research on Aadhaar reveals two important points about the datafication of anti-poverty programmes. First is their technical rationale, and second are the political consequences that the new data architecture produces. he efforts made over the last two decades. We suggest that there are four key areas where further action is necessary.

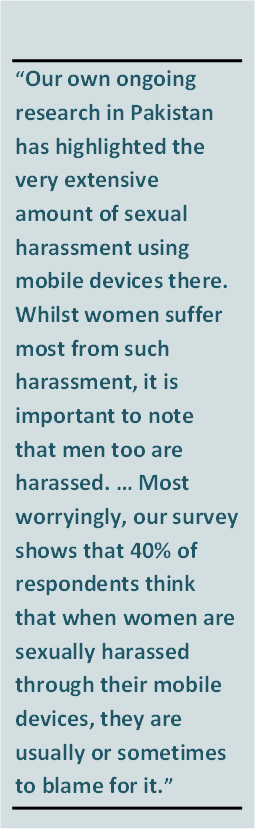

he efforts made over the last two decades. We suggest that there are four key areas where further action is necessary. Interestingly, preliminary results from our online survey suggest that although social media are used for harassment, most often it occurs through calls and text messages. The implications of posting images on social media have recently been highlighted by the apparent

Interestingly, preliminary results from our online survey suggest that although social media are used for harassment, most often it occurs through calls and text messages. The implications of posting images on social media have recently been highlighted by the apparent

nergies using existing ICT infrastructures, embracing differences between developed and developing countries without necessarily trying to change them, promoting open and inclusive innovation and redefining financial inclusiveness beyond money could all really bridge gaps in the global digital economy.

nergies using existing ICT infrastructures, embracing differences between developed and developing countries without necessarily trying to change them, promoting open and inclusive innovation and redefining financial inclusiveness beyond money could all really bridge gaps in the global digital economy.